Once upon a time, intrepid travelers drove their early automobiles on planks hand laid across a shifting sea of sand dunes between Yuma, Arizona, and the alluring ocean breezes of San Diego beyond.

The precarious stretch became known simply as The Plank Road. Although in service for only 11 years, The Plank Road continues to live large in the annals of Southwest transportation and local lore.

How did such an audacious route happen? Who was behind the scheme? What was the motivation?

What was it like to travel The Plank Road? What replaced The Plank Road? What happened to remnants of the old Plank Road? This article attempts to answer those questions.

America's so-called "Little Sahara" is the nation's largest contiguous area of sand dunes. The dunes formed thousands of years ago from wind-blown remnants of an ancient lake formed by the meandering Colorado River. The searing summer sands rebuffed human encroachment. The loose, deep sand made early travel next to impossible. Lack of water compounded perils of the shifting sand dunes. Early travelers simply avoided the 45-mile-long dune field by detouring into Mexico or around the north tip. Throughout decades of early settlement, pioneers considered the dunes an impenetrable obstacle. So what happened to cause The Plank Road to be pushed across the dune field?

In a nutshell, the sand dunes were conquered largely because of a single-minded, natural-born salesman---Ed Fletcher. Fletcher came to San Diego in 1888 at the age of 15 with $6.10 in his pocket. He quickly parlayed pocket change into lifelong economic and political success. Fletcher was like a pied piper for "all things San Diego" and had an uncanny knack for raising lots of money for his many pet projects and causes. Fletcher leveraged the antagonism between San Diego and its rich northern neighbor, Los Angeles, to fan the flames of fervor for a road that would bring cash-laden tourists directly to San Diego first instead of that big city up yonder.

Of course, most folks thought Fletcher had gone daft when he suggested a road across the sand dunes. One of his scornful critics in Los Angeles challenged Fletcher to a 1912 race coinciding with the Cactus Derby. Fletcher recruited two reporters and obtained a six-cylinder, 30-horsepower, air-cooled Franklin touring car. He lined up a teamster with six mules to drag him across the dunes. As luck would have it, heavy rains fell when the race got underway and Fletcher was able to motor across the dunes without assistance. He beat his rival to Phoenix by over 19 hours!

This victory emboldened Fletcher and he used both his showmanship and salesmanship to add momentum to the growing support for a road across the dunes.

Of course, most folks thought Fletcher had gone daft when he suggested a road across the sand dunes. One of his scornful critics in Los Angeles challenged Fletcher to a 1912 race coinciding with the Cactus Derby. Fletcher recruited two reporters and obtained a six-cylinder, 30-horsepower, air-cooled Franklin touring car. He lined up a teamster with six mules to drag him across the dunes. As luck would have it, heavy rains fell when the race got underway and Fletcher was able to motor across the dunes without assistance. He beat his rival to Phoenix by over 19 hours!

This victory emboldened Fletcher and he used both his showmanship and salesmanship to add momentum to the growing support for a road across the dunes.

In the meantime, Fletcher gained a bulldog ally in Edwin Boyd, an Imperial County Supervisor who lived in Holtville. Boyd (right with wife in 1950) was the originator of the idea to lay planks down across the sand to make a road. Once Fletcher saw the genius in Boyd's ideas, he was off to the fundraising races. In hardly any time, Fletcher raised enough money to have a boatload of Oregon lumber shipped south and carried to the edge of the dunes. By that time, a relatively narrow width of the dunes had been identified. The dunes there were much lower in height than elsewhere in the sprawling sea of sand. Likewise, the route even had a little "valley" that was flat with far fewer dunes. Boyd bullied, cajoled and sweet talked his friends and associates into "volunteering" to help build the first Plank Road in 1915. He also was able to use some scant funding to hire laborers. The Oregon planks were carefully attached to each other and strung across the dune field like some sort of boardwalk for cars. The first Plank Road opened to much fanfare. Sadly, the poorly-designed, flimsy and precarious first draft Plank Road was doomed to failure by both the relentless winds and the toll wrought by heavy traffic. It lasted only a few months.

Undaunted, Fletcher somehow convinced the newly-formed California Highway Commission to fund a much better Plank Road. Thousands of railroad-tie-style treated timbers poured into a hastily erected fabrication facility at the whistle stop Ogilby on the Southern Pacific railroad east of the dunes. Large sections of Plank Road weighing 1,500 pounds each were built at the Ogilby facility. Up to four such sections could be hauled to the dunes by plodding horses and mules. The sections were so heavy and cumbersome that additional apparatus had to be erected just to offload and position the sections on the roadway.

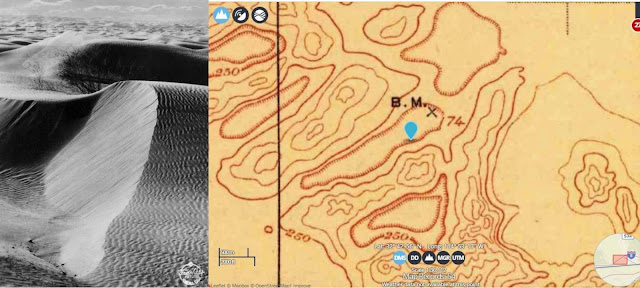

In the USGS topo map clip above, Ogilby is in the red circle. The red line marks the approx. location of the Plank Road. Although it was slow going by wagon between Ogilby and the road construction area, the distance was short. Animals could be fed and watered back at Ogilby. (NOTE: Yuma is at lower right on this map.)

As you can easily see from this photo, the timbered sections used in the Plank Road were very stout and well-constructed. They were clearly engineered to take a beating from heavy traffic volume and truck weight and they actually performed very well...except when the wind went on a tear.

From the few reports written by or recorded from travelers of the Plank Road it was a bone shaker. One woman said it was far better than a visit to the chiropractor. Vehicles crept across the Plank Road, often as slow as 2-3 miles per hour. The one-lane reality of the Plank Road created bottlenecks that often caused tempers to boil over more than radiators. One report indicates fist fights were a common cause of delay on the Plank Road. Once a line of 20 cars was held up by a lone driver who refused to back up to a turnout. Frustrated motorists simply picked up his car and placed it on the sand beside the road. After their 20 cars passed, they courteously placed his car back on the planks.

Over the past 100 years, the Plank Road has grown in the retellings of travel across there dunes until it has assumed a larger-than-life role in the imaginations of modern travelers. In truth the Plank Road was perhaps 6-8 miles at its longest. The "open valley" indicated on the map above was flat and stable enough to be oiled instead of planked.

Many newspaper "road reports" from the early 1920's indicated the Plank Road was in good shape but travel between Holtville and the Plank Road was "rather difficult."

Many newspaper "road reports" from the early 1920's indicated the Plank Road was in good shape but travel between Holtville and the Plank Road was "rather difficult."

As traffic volume inevitably grew by leaps and bounds due to insatiable demand for automobiles, the arcane behaviors and "rules of travel" required to safety navigate the Plank Road became untenable. Something clearly had to be done.

As the Plank Road aged so, too, did ongoing maintenance tasks become ever more daunting. Ferocious storms rolling in off the Pacific often brought gale force winds and heavy rains which wrecked havoc with the Plank Road. The California Highway Commission wisely decided to create a "real road" in the mid-1920's. Road construction technology had improved by leaps and bounds from the mid-teens to the mid-20's. Far more custom machinery and efficient engineering could be brought to bear on once vexing road route and construction issues.

Prior to beginning the mid-20's construction of what would become US Highway 80, engineers conducted a long study of the sand dune behavior. Their data showed that a road elevated much higher than the old Plank Road would be far less susceptible to both wind erosion and sand deposition. They were quite correct. In its early years, US 80 was not closed by either of the bug-a-boos that doomed the old Plank Road.

For many years, the old Plank Road ran more or less alongside of US 80, a visible reminder of the hardships and perils of early travel across the sand dunes.

Famed Southwest Photographer Burton Frasher loved to create images of sand dunes. His dune portraits from Death Valley remain some of the best in that genre. Frasher occasionally stopped to capture the dunes draped across the old Plank Road, giving us modern highway heritage fans an endearing image of a fading chapter of transportation history.

Eventually the remnants of the old Plank Road succumbed to the ravages of wind, water, sun and firewood-hungry dune-runners.

stepped forward to join forces and preserve pieces of the Plank Road.

For discussion and a partial list of our sources see:

https://azitwas.blogspot.com/2019/01/plank-road-sources.html

The old photo at left in this pair was the one that prompted our study of the Plank Road. "Bloo" from the Antique Automobile Association of American (AACA) Forum identified the car for us. He said:

"That's a Studebaker. It is possibly a 1913, not an SA-25 like mine (those still had acetylene lights), but possibly a "35" or a "6". I can't see the steering wheel. In 1913, it was still on the right. I think I see a spare tire on the right side of the car, which argues for right hand drive. There was no door on the drive side, so it wasn't blocking anything. I believe 1914 had left hand drive for the US market.

Here's a 1913 "35" and then "Bloo" provided the photo at right.

In closing this discussion of the Plank Road we would like to add our Thanks and a Commendation for "work well done" to all members of the AACA Forum who keep alive the memories and details of early automobiles. The men and women of that esteemed Association are a true credit to the Spirit of our Nation's Transportation Legacy!

In closing this discussion of the Plank Road we would like to add our Thanks and a Commendation for "work well done" to all members of the AACA Forum who keep alive the memories and details of early automobiles. The men and women of that esteemed Association are a true credit to the Spirit of our Nation's Transportation Legacy!

For discussion and a partial list of our sources see:

https://azitwas.blogspot.com/2019/01/plank-road-sources.html

THANK YOU FOR READING!

John Parsons, Rimrock, Arizona

John Parsons, Rimrock, Arizona